Jul. 20, 2018 • By Bill Kohlhaase • Santa Fe New Mexican

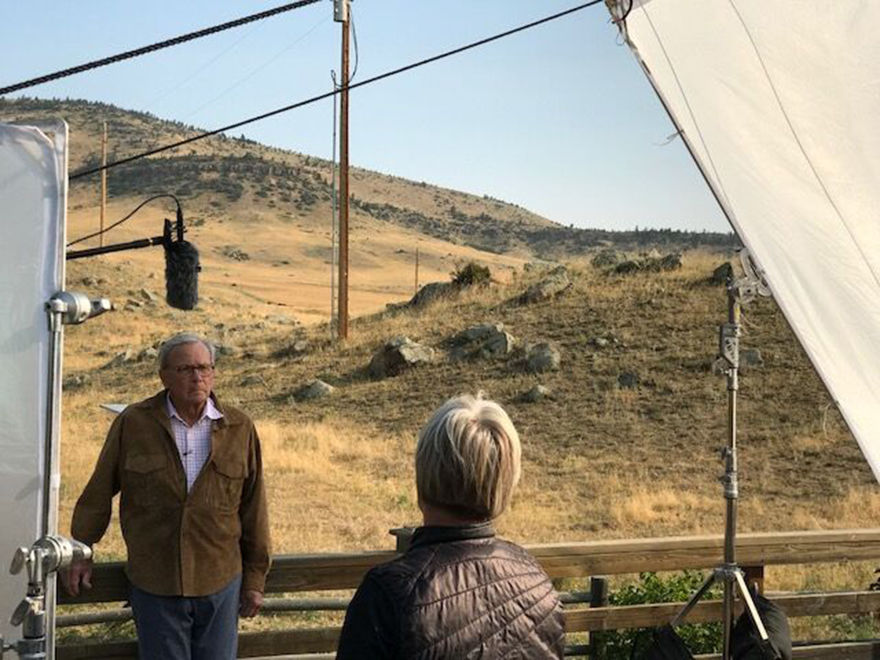

When it was first brought to him, Grammy- and Oscar-winning composer-arranger-producer-pianist Dave Grusin didn’t think much of the idea of doing a documentary film on his weighty career. “It wasn’t a big thing on my radar,” the eighty-four-year-old Grusin said. “I just didn’t think people would be interested enough to go see it.” The film’s director, Barbara Bentree, thought differently. “He didn’t think anyone would be interested — ha!” the Santa Fe-based musician and filmmaker said. Bentree and her husband, jazz pianist John Rangel, first suggested the idea to Grusin in 2015 on a visit to Grusin’s home in McLeod, Montana (he also has a home in Santa Fe). “It took us four months of meetings to convince him that we could do it and that it should be done,” Bentree continued, adding that Grusin’s wife Nan Newton coming on as co-producer also played a major role. The thing that finally convinced him, Grusin explained, was his affinity for Bentree and Rangel. “They’re great folks, great musicians. They live in Santa Fe and are a big part of the community there. How could I say no to these people?”

The result, Dave Grusin: Not Enough Time, will be previewed Sunday, July 22, at the Lensic Performing Arts Center as part of the New Mexico Jazz Festival. The event also includes a rare chance to see Grusin performing solo. The film’s first preview came earlier this month at the Montreux Jazz Festival in Montreux, Switzerland, with such luminaries as Quincy Jones, who also appears in the film, in attendance. Grusin, who said he saw a “rough assembly” of the film early this year, will be seeing the completed project for the first time at the Lensic. “The title came from my main complaint that went with scoring films. I never felt like I had enough time. From the moment you get the film’s final cut, there’s usually not a lot of time before they need it back. So that became a working motivation for me. People ask me, ‘How do you get your ideas?’ Most of them came from the idea that the work is due next week. I had a fear of deadlines.”

Beginning in the 1960s, those deadlines came at a rapid pace. Over decades, Grusin scored some 60 feature films, including On Golden Pond, Three Days of the Condor, The Firm, Tootsie, and The Fabulous Baker Boys. He earned an Oscar for his score to director Robert Redford’s 1988 film The Milagro Beanfield War, as well as Academy Award nominations for scoring Heaven Can Wait, The Champ, On Golden Pond, The Fabulous Baker Boys, Havana, and The Firm, which featured Grusin as solo pianist. He was also nominated for Best Original Song, “It Might Be You,” from Tootsie, with lyrics by Marilyn and Alan Bergman. He wrote music for dozens and dozens of television episodes, including the well-remembered themes for Good Times, Maude, and St. Elsewhere.

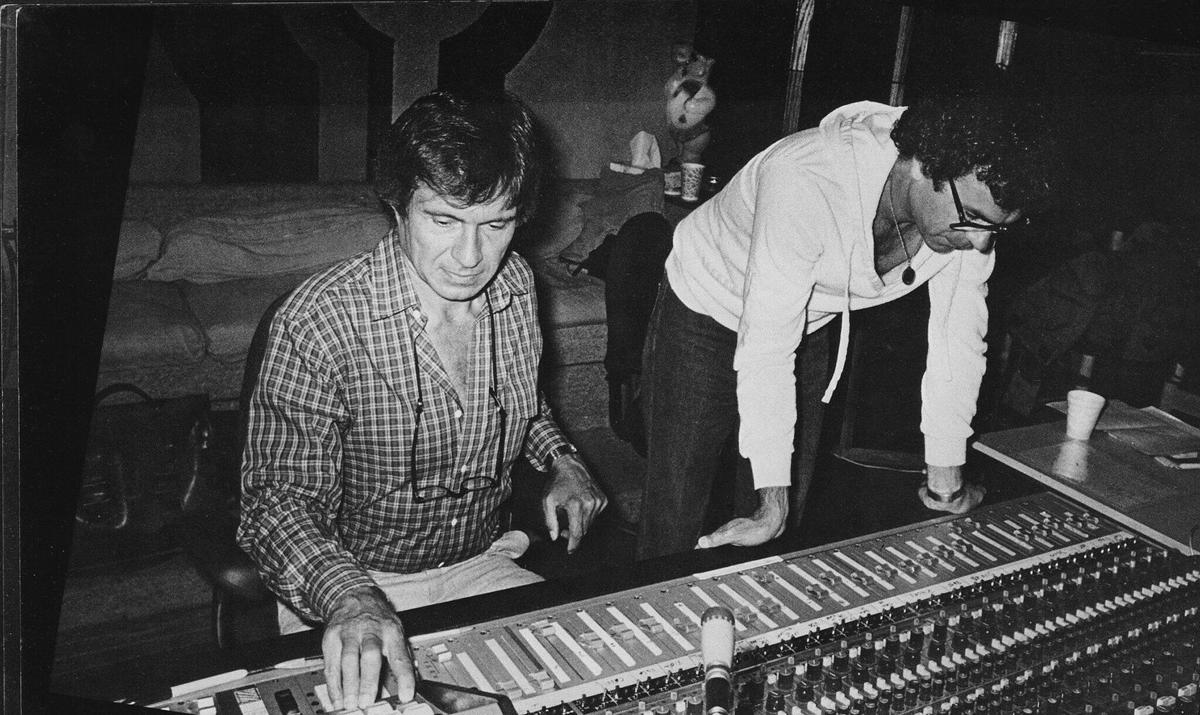

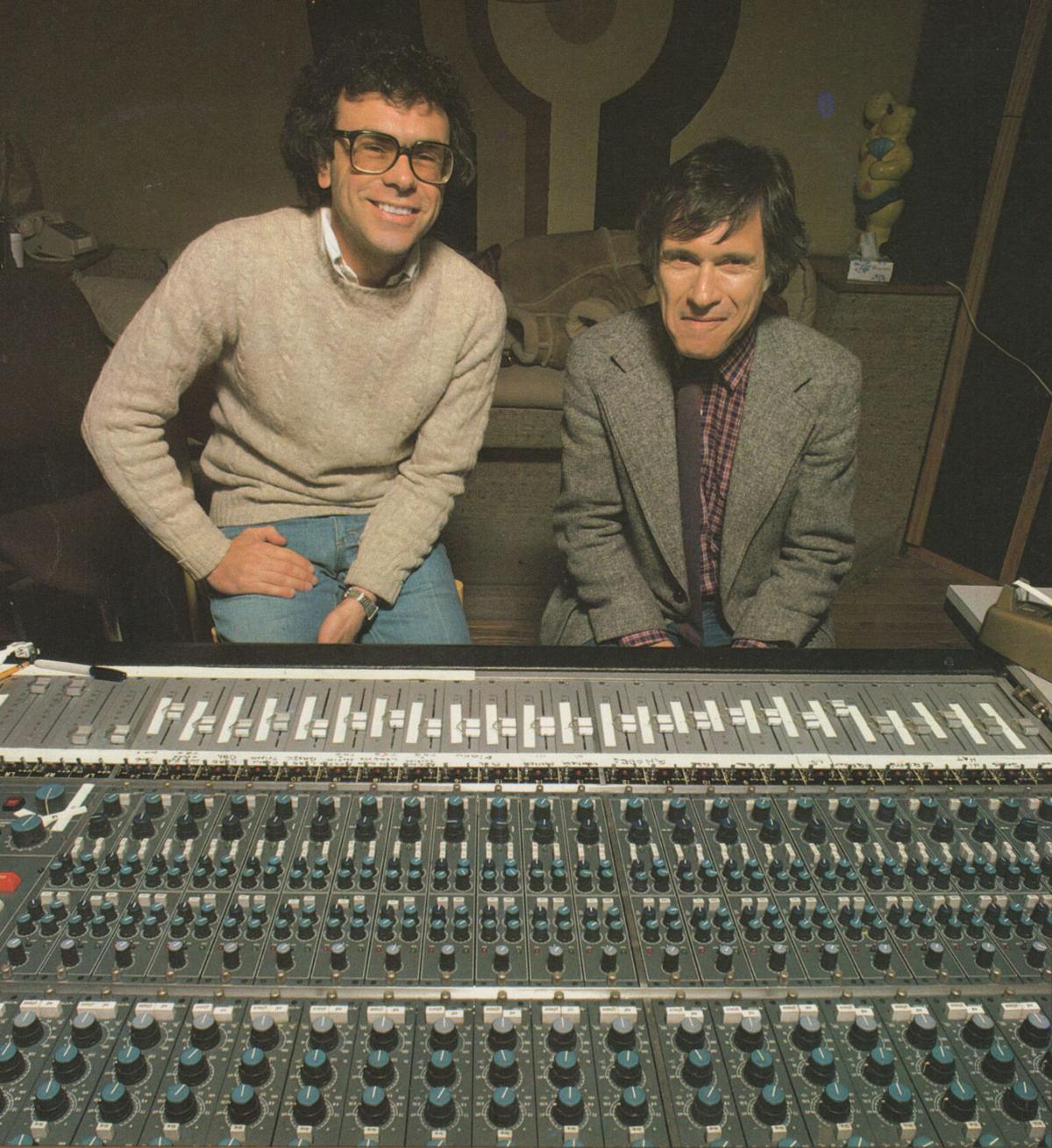

One career wasn’t enough. Grusin and his buddy from The Andy Williams Show, Larry Rosen, started Grusin Rosen Productions in the ’70s, and began releasing records for Arista as Arista/GRP. They went independent in 1982; as GRP, the record label became an industry leader in contemporary jazz and a pioneer in digital recording. Grusin, who remained a performer, produced many of the label’s recordings, including his own. His deep and varied career came of what he called “serendipitous” relationships, with people he was just lucky to meet. “I’ve often felt like one of those shiny steel balls in a pinball machine, bouncing off all these different things,” Grusin said. “My life’s been a reaction to the circumstances determined by the people and opportunities I’ve bumped into. Nobody’s been luckier.”

But there’s been more than luck at play. In addition to his craft as a musician and a composer, Grusin has cultivated and maintained fruitful relationships with musicians and entertainment professionals who have utilized his skills, including such figures as director Sydney Pollack and writer-producer Norman Lear (“I still talk to Norman from time to time,” Grusin confided). A host of personalities are interviewed in the film, both from the world of music, including Jones, the late producer Tommy LiPuma, and lyricists Marilyn and Alan Bergman, and from the world at large, including Tom Brokaw, Michael Keaton, and writer Thomas McGuane (Grusin’s neighbor in Montana). They attest to Grusin’s friendliness and modesty, as well as his work ethic. “Dave is a very humble guy,” said director Bentree.

Grusin, a Littleton, Colorado, native who admits to still harboring a desire to become a large animal veterinarian, was encouraged by his father to pursue music. He was preparing to take classes at New York’s Manhattan School of Music when an acquaintance from his days as a music student at the University of Colorado - Boulder called to tell him that vocalist Andy Williams was looking for a piano player to go out on the road with him. “I needed a gig to support myself, so I met Andy and did a little audition, and that worked out for him — and it certainly worked out for me,” Grusin said. “That became my gig for several years and I never did make it into class.” The drummer in the Williams group was Larry Rosen, his future business partner.

Another contact Grusin made through Williams’ show was one of the show’s producers, Bud Yorkin. Yorkin gave Grusin his first film work, scoring Yorkin’s Divorce American Style, a mid-’60s farce starring Debbie Reynolds, Dick Van Dyke, and Jason Robards. The script was written by Norman Lear. “It was amazing to get that kind of film, having never done a feature film before. It’s responsible for my whole career. It was an early indication of how relationships work in that world.”

Another fortuitous contact, one he sought out, was with composer Henry Mancini. “Mancini was an inspiration before we even met,” Grusin said. “When I first thought about writing music for film, I thought that it didn’t have to be like the more traditional soundtracks. People like André Previn were writing more modern stuff and jumping into areas of jazz. I thought maybe that was the kind of music I had a shot at doing.” He took some of his music to Mancini and the composer graciously agreed to talk about it. Mancini became his principal mentor. “When I got stuck on something, he wouldn’t tell me what to write but would talk philosophically about what he would do to solve it. If there was a chase scene that needed to be made more exciting, Hank would say, ‘You don’t have to write a lot of notes to do that. Just find a musical texture and let it complement the sound effects. You don’t need to make a statement to explain the situation. That’s what the sound effects do.’ To hear somebody like Hank say that was very enlightening.”

The GRP label came at a time when jazz and recording were changing. GRP developed a recognizable musical stamp, both in the material and artists it recorded, and with its digitally documented sound. Grusin, who did most of the musical and business side of production, gives Rosen credit for the label’s integration of digital recording techniques. “The recording business isn’t anything like what it used to be. I don’t even know if there is a business. We used to make albums and wonder how to promote them. If that’s going on today, I don’t see it. I don’t understand how you can control your life and your product. If I were younger, that’s exactly what I would be trying to figure out.”

Grusin, influenced by his own musical tastes, can take credit for the sound he brought to films at a time when electronic instruments, especially synthesizers, were being introduced to soundtracks. “That was always fascinating to me — how to use the technology to enhance what we were trying to do acoustically all those years. I actually used to think of synthesizers as another section of the orchestra with a different kind of function. Sonically, [the synthesizer] brought a whole new category of sonic choices, particularly as it was being developed.”

Grusin said he doesn’t perform much anymore, but his schedule shows something different. After having recently played in the Ukraine with guitarist and longtime collaborator Lee Ritenour, he returns to Europe again this summer to make appearances with Ritenour as well as to present a program of music from West Side Story. He’ll also be playing at a few of the film’s previews later in the year, including one at the Monterey Jazz Festival. He performed a benefit in Big Timber, Montana, for the Sweet Grass Arts Alliance on July 14, calling it a rehearsal of his upcoming solo appearances. “I really don’t do a lot of practice anymore. Things don’t stay the same as you get older — they begin deteriorating in different ways. I learned to do all these things at the piano naturally, and when that stops working, you have to find ways to fix it.”